Do you ever feel like you’re constantly trying to fix things, but they are out of your hands? Like you’re responsible for everything, and nothing ever gets better? Do you feel chronic emotional pain trying to make things better?

- Anxiety

- Overwhelm

- Emotional burnout

- Failed relationships

- Lack of peace or purpose

- I am sick and tired of being sick and tired

You’re not broken. You’re just confused about what you can actually control and what you can’t. The ancient Stoics had a clear answer. It might change your life; it changed mine.

What You’ll Learn in This Post

- Why your definition of freedom may be sabotaging you

- The 2,000-year-old rule for peace of mind

- A simple method to sort what’s in your control

- Real-life examples: job interviews, friendships, even mowing lawns

- How this idea connects to modern therapies like CBT and ACT

Freedom Comes Before Self-Control

Before we dive into control, we need to discuss freedom. Not the “Fourth of July” kind or the “nobody tells me what to do” kind. We mean the real thing. Without freedom, there can be no control. With a bad definition of “freedom,” attempts to exert control will be misdirected and fail.

To the ancient Stoics—and most classical thinkers—freedom wasn’t about doing whatever you feel like. It was about mastering yourself. To the ancients, authentic freedom is having the strength to choose what’s right, even when it’s hard. This freedom aligns your thoughts and actions with reason, virtue, and the natural order of things.

That’s a long way from today’s version, where freedom often gets reduced to “no rules, no limits, no regrets.” Do whatever you want, whenever you want, no matter the consequences. That sounds exciting—until it breaks your life.

Two Very Different Freedoms

Let’s compare the old and the new side by side.

Real (Classical, Stoic) Freedom:

- “Freedom is obedience to reason.”

- “The only true freedom is mastery of self.”

- “Freedom is the power to choose the good, even when it’s hard.”

- “To be free is to live in harmony with nature and God.”

Modern ‘Freedom’ (The Illusion):

- “Freedom is doing whatever I want, whenever I want, regardless of the truth, the cost, or the consequence.”

- “No rules, no limits, no regrets.”

- “My truth, my way.”

- “Chaos masquerading as liberty.”

One view leads to maturity, peace, and purpose. The other often leads to anxiety, regret, and broken relationships.

Why This Ancient Stoic Idea Still Matters Today

If we start with the wrong definition of freedom, everything else gets messed up—including our idea of control. We start thinking we should be able to control everything: people, outcomes, feelings, even the future. But that’s not how reality works.

The ancient Stoics saw this clearly. They taught that peace and power come from knowing what’s up to you—and what isn’t. That’s the foundation for real freedom.

Where We’re Headed

Imagine trying to cross a river on slippery rocks. Step on the wrong one, and down you go. But step on the dry, stable rocks—solid, ancient truths—and you can safely cross.

That’s what this blog is about: showing you the firm ground under your feet. If you’ve ever felt stuck, anxious, or overwhelmed, this shift in mindset might be the most helpful thing you’ve heard in a long time.

Do You Know Where Your Control Is?

This idea goes back thousands of years. Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher, said it better than anyone I’ve read — and he’s profoundly shaped my thinking. Epictetus (c. 55–135 CE) was a Greek Stoic philosopher in the Roman Empire. He didn’t start life with privilege—he was born a slave, lived with a physical disability, and lost almost everything before becoming a philosopher.

But through hardship, he discovered something powerful: “Some things are up to us and some are not.” (Epictetus, Enchiridion 1) As stated in modern parlance, you can’t control the world, but you can control how you respond to it. His tough-earned wisdom still speaks today, especially when life feels unfair, unpredictable, or overwhelming.

It doesn’t sound profound at first—but each word carries weight.

“Up to us are opinion, impulse, desire, aversion — in short, whatever is our own doing. Not up to us are our body, property, reputation, office — in short, whatever is not our own doing.” (Epictetus, Enchiridion 1)

On first reading Epictetus, I felt panic as the “Up to Us, Our Own Doing” list didn’t seem applicable to modern me. And the things I worried about were all on the “Not Up to Us, Not Our Own Doing” list. The following lists show these in a contemporary manner.

Up to us, our own doing, in our control:

- Our thoughts

- Our judgments

- Our values

- Our intentions

- Our actions

Not up to us, not our doing, not under our control:

- Other people’s opinions or choices

- Outcomes of our actions

- Accidents, illness, nature

- The past or future

- Whether things work out the way we hope

We become free by:

- Focusing on things within our control

- No longer focusing on things outside our control.

Six Reasons to Learn What’s Really in Your Control

“If you want to be free, then wish for nothing that depends on others; otherwise, you are necessarily a slave.”(Epictetus, Discourses 4.1.54)

Why should I care about this control stuff when the ‘Not Up to Us’ list is where all the real stuff happens? The “up to us” and “not up to us” dichotomy is vital for many reasons:

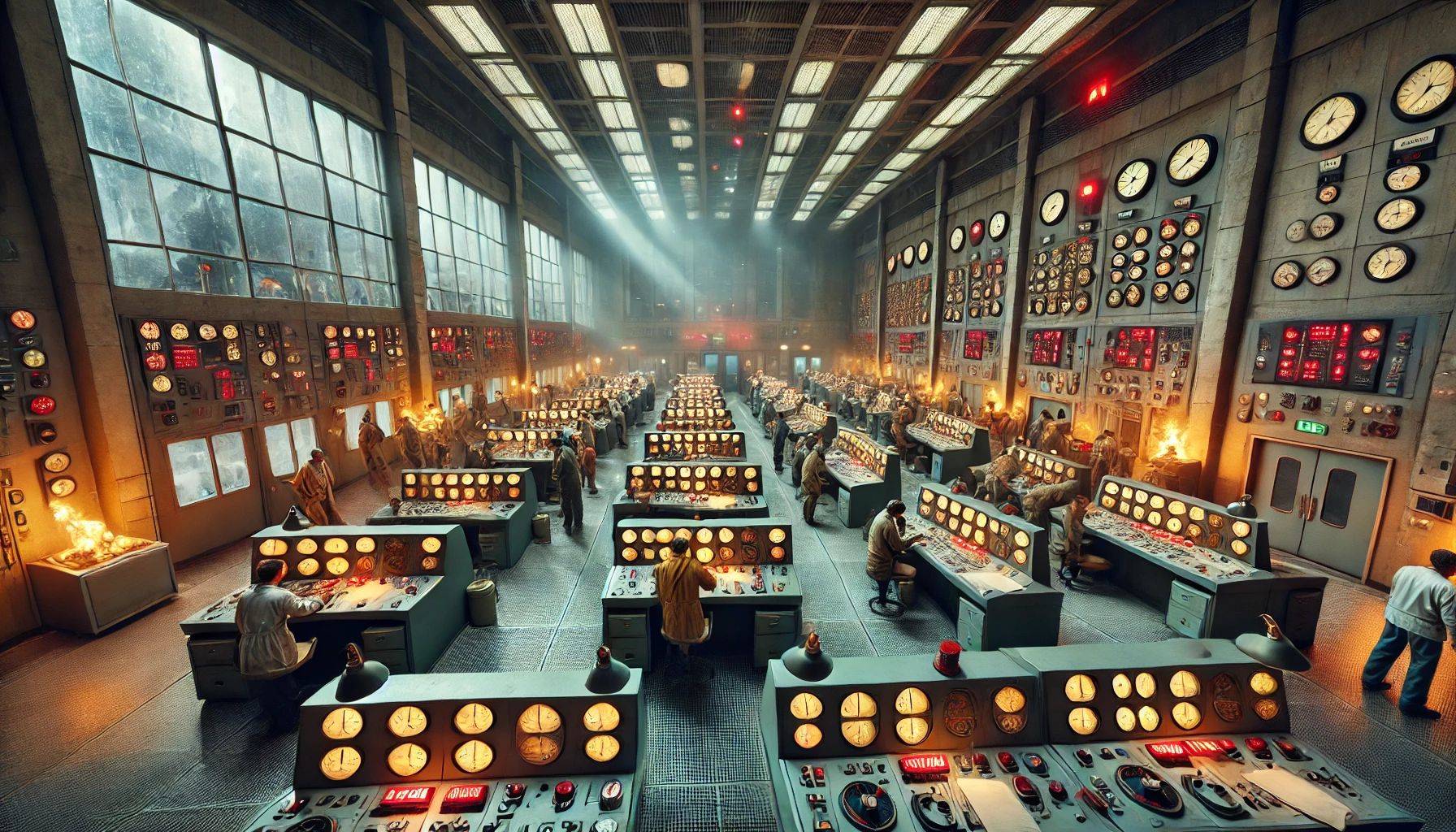

1. Because What’s “Up to Us” Is Where All Our Power Actually Lives

The “Up to Us” list may look small… but it’s the engine room of everything you do. Your thoughts shape your feelings. Your judgments guide your decisions. Your values steer your life. It’s quiet power — but it’s real power. Everything else is weather.

2. Because Clarity Helps You Stop Wasting Energy

When you realize outcomes, other people, and the future aren’t yours to command, you can finally stop wasting energy trying to manage them. That lets you redirect your focus onto what you can steer: your next step, your next word, your next attitude.

3. Because the “Not Up to Us” List Isn’t Yours to Carry

We break under the weight of things we weren’t built to control. Trying to carry the future, the past, or other people’s choices is like strapping a refrigerator to your back and wondering why life feels heavy. The Stoics hand you permission to set it down.

4. Because the “Not Up to Us” List Is Real — But Not Yours to Fix

Illness, accidents, rejection — they do happen. They matter. But you meet them best by bringing your values and intentions to the table. That’s how you show up — and that part is yours.

5. Because the “Up to Us” List Is How You Live with Integrity

You can’t always win. You can’t always fix. But you can choose courage, humility, kindness, perseverance. That’s not small — that’s what makes people trustworthy, admirable, and wise.

6. Because the “Up to Us” List Is Where Freedom Hides

Modern life defines freedom as “getting your way.” Epictetus defines it as “ruling yourself.” You can’t always get what you want — but you can always choose how you respond. That’s real freedom, the kind nobody can take from you.

Let the Wise Ones Speak

From Epictetus:

“It is not things themselves that disturb us, but our opinions about them.” (Epictetus, Discourses 1.1.4)

The “things themselves” are those things like circumstances, environment and external things over which we have no control. What we think about them and how we react are things that are up to us. We will soon go into details on this.

Marcus Aurelius was a Roman emperor, Stoic thinker, and the most famous student of Epictetus.

“If you are pained by any external thing, it is not this thing that disturbs you, but your own judgment about it.” (Meditations, Book 8.47)

Knowing what you can control and can’t is a giant step to freedom, peace, and serenity. The commonly recited phrase from the Serenity Prayer used in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings is:

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Summing Up What is Up to Us

Why should I care about what is “in my control” and what isn’t? This sounds like the impractical questions that ancient philosophers thought up. Like those questions that give us headaches, make us dizzy, and have nothing to do with “real” living.

Great question, important question. The question is vital to living at peace with those around us and within ourselves, leading to profound serenity. The control debate has everything with our modern living, even if it seems couched in ancient wisdom literature.

Modern psychological therapies are based on the Stoic idea of control, no control, and knowing the difference. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is based on this idea and knowledge at its foundation, as are some more recent therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Examples of Control vs. No-Control

The following shows the difference between the “Up to Us” and “Not Up to Us” items for three common life experiences that I have had to struggle with. When I confused the uncontrollable things as being things I should control and was responsible for, then each of these situations became an emotional and stressful disaster.

Job Interview to Get a Job

Up to Us (Always):

- Preparing thoroughly (researching the company, reviewing common questions)

- Showing up on time

- Dressing appropriately

- Speaking clearly and honestly

- Asking thoughtful questions

- Managing our mindset before and during the interview

- Responding with calm under pressure

- Demonstrating our character, values, and willingness to learn

Not Up to Us:

- Whether the interviewer likes us personally

- Whether another candidate is more experienced

- The number of candidates interviewing for the same job

- The company’s internal hiring decisions or budget

- Whether they get back to us quickly (or at all)

- Whether we get the job offer

Key Confusion Point:

Guilty as charged. I hate interviewing and job searches. Before I learned about up-to-me versus not-up-to-me distinction, every job interview for which I “lost the job” (and there were many) was my fault and failure. I would spiral into self-loathing and depression. This emotional low lasted days to weeks before I could recover.

Once I started focusing on what was “up to me” and realizing the other things were out of my control, my interviewing became more successful in getting job offers. And when I didn’t get an offer, I felt at peace about the entire process. I felt a little sad, but none of the “crash and burn” spirals from the past.

2. Hoping That a Particular Person Will Become Our Friend

Up to Us (Always):

- Being kind, respectful, and approachable

- Inviting the person to talk, hang out, or share experiences

- Showing interest in their life (without being intrusive)

- Setting healthy boundaries

- Being patient and emotionally grounded, whether or not they respond warmly

- Being honest and consistent

Not Up to Us:

- Whether they like us back

- Their past experiences and biases

- Their current social/emotional capacity

- How they respond to our invitation

- Whether they prioritize friendship right now

Key Confusion Point:

We often try to earn or control someone’s affection — but their feelings, readiness, and choices are their own. Before I learned this lesson, making friends was like job interviews, with the same sad responses. Once I learned what is “up to me,” the results were like the latter job interviews. More success and less trauma.

3. Teenager Setting Up a One-Person Lawn Mowing Service

Up to Us (Always):

- Creating flyers or marketing the service

- Setting fair and clear prices

- Showing up on time and doing quality work

- Being polite and reliable with customers

- Keeping equipment clean and maintained

- Saving or spending money wisely

- Learning from mistakes and adjusting

Not Up to Us:

- Whether neighbors say yes or no

- Whether a competitor undercuts them

- Poor weather that cancels a day’s work

- A mower breaking down unexpectedly

- How much total money is earned by summer’s end

Key Confusion Point:

The teenager may think that “making $500” is their goal, but the actual income lies outside their control. In most endeavors, the goal itself exists beyond our sphere of influence. However, there are numerous important factors that we can control: effort, service quality, follow-up, follow-through, preparation, research, and so on.

By focusing on these controllable factors, we significantly enhance our chances of reaching our goal. Regardless of whether we achieve it, we will become more capable, reliable, trustworthy, intelligent, wise, and ultimately, more valuable. The more valuable we become, the better the opportunities we encounter at work and in life.

Homework

I’m sorry, but there is no escape. I use this exercise and find it highly beneficial.

- On a piece of paper, write down the name, situation, person, or circumstance that fits these:

- This evokes strong emotions (anger, fear, pain) every time you think about this.

- This never resolves; it keeps returning (like constantly burping lousy pizza).

- This is something of yours, not belonging to someone else.

- Make two columns on the paper. Or divide the paper into a top and bottom section (my favorite method). Label one column or section as “Up to Me” or “Within My Control.” Label the other as “Not Up to Me” or “Outside My Control.”

- Write all the things you can think about in each section. Use the earlier examples for ideas on control versus no control.

We are Going to the Movies

The movies are confused about the “under my control” and “not under my control” categories, frequently placing blame and responsibility in the wrong places. The movies artistically present this confusion with visual impact, great actors, and compelling dialogue. In the next blog, we will be a “movie philosopher.” This is like a movie critic, but we will uncover the philosophical confusion so common everywhere.

Lights, camera, action!

Try the homework. What’s one thing you’re carrying that isn’t yours? Write it down right now. That might be the start of real peace. If it changes something for you—even a little—share it with someone you trust.

See you at the movies…

AI Assistance Statement: This article was drafted with assistance from ChatGPT and edited by First Elder. Grammarly was used to enhance grammar, readability, and style.